George Vardas Unveils: The Dilemma of the National Museum of Denmark and the Resonance of “Non Audemus”

The National Museum of Denmark’s recent resolution to retain the revered Parthenon Sculpture fragments has sparked both consternation and controversy. These fragments, bearing historical significance and embodying the artistic legacy of ancient Greece, stand at the crossroads of cultural identity and global collaboration. While some hail this decision as a respectful preservation of history, others, including myself, stand in dismay at what feels like a missed opportunity for restorative justice.

It is disheartening to witness the National Museum of Denmark perpetuate the contentious legacy of cultural appropriation and colonial acquisition. By choosing to retain these fragments, they perpetuate an unresolved narrative of contested ownership, denying the rightful context and reunification of these treasures with their origins—a decision that falls short of honoring the heritage they represent.

With meticulous research and thoughtful insight, George Vardas navigates the complexities surrounding this pivotal juncture in cultural preservation. His discerning analysis invites us to contemplate the implications of the museum’s choice, sparking a dialogue that transcends geographical boundaries and speaks to the essence of heritage stewardship.

I extend my sincere appreciation to George for graciously incorporating my perspective into his insightful narrative. It’s an honor to contribute to such an esteemed dialogue, adding a layer of diverse insight to this crucial discussion surrounding the Parthenon Sculpture fragments.

As George Vardas masterfully dissects this critical juncture, in his forthcoming article, one can’t help but resonate with the words of Seneca:

“Non quia difficilia sunt non audemus, sed quia non audemus difficilia sunt.” (Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger Seneca, Epistulae Morales 104.26)

„We do not dare because things are difficult, but things are difficult because we do not dare.”

It’s in our audacity to confront these challenges that the path to a more just and inclusive cultural landscape begins.

For those eager to delve deeper into this discussion, I encourage you to scroll down and read George’s article in Greek City Times. We are indebted to him for graciously permitting the publication of his work here, fostering a platform where diverse voices converge to contemplate and appreciate cultural heritage.

Mag. Alexandra Pistofidou,

Founder and Chair of the Austrian Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures

The Parthenon Sculptures: “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”

William Shakespeare’s famous line from Hamlet that something is not right comes to mind with the news that the National Museum of Denmark, after “careful consideration”, has refused requests from the Acropolis Museum in Athens to return three fragments of the Parthenon that are currently on display in Copenhagen.

According to the Danish Museum’s director, Dr Rane Willerslev, the sculptural fragments are of greater importance to the National Museum than if they were sent to Greece, noting that the majority of the surviving Parthenon sculptures are divided between London and Athens and the three fragments in Copenhagen have “one particular role for Danish cultural history”.

I have previously written about the broken fragments of the Parthenon, including the pieces in Copenhagen, and the growing imperative for their return.

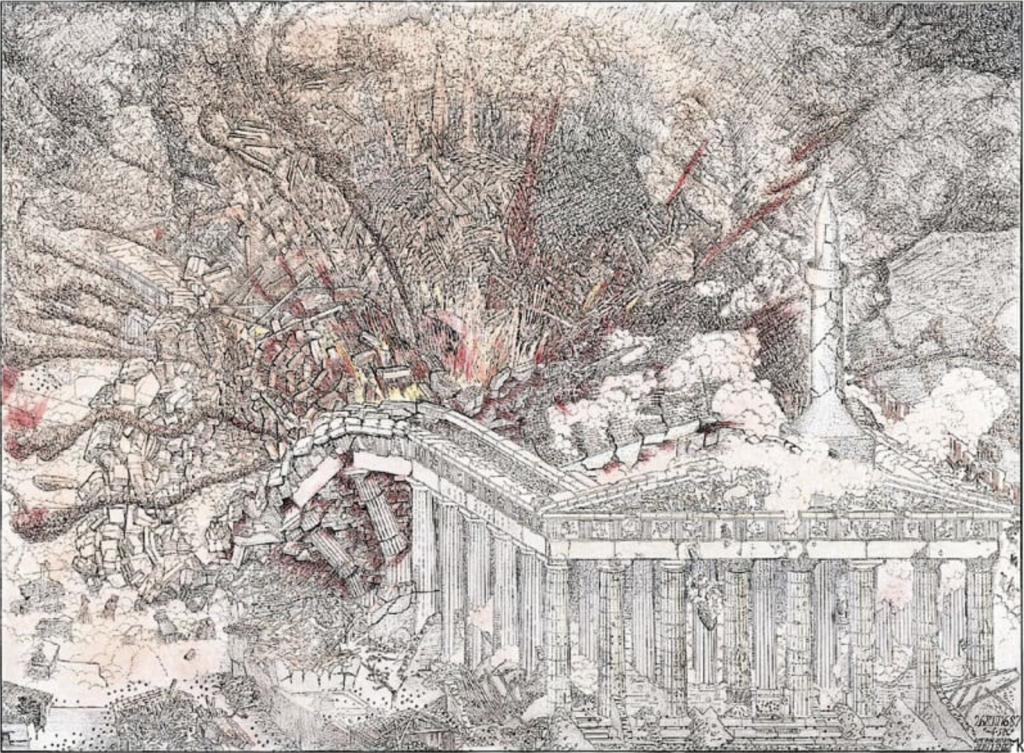

In order to examine the claims now made by the National Museum of Denmark we need to go back in time to a fateful day in September 1687 when the then Ottoman-controlled Parthenon was famously blown up by mortar shells fired by the surrounding Venetian forces under the command of Francesco Morosini.

The explosion caused extensive damage to the temple, blowing out the central part of the walls and a number of columns and bringing down much of the decorative Parthenon frieze as well as pedimental sculptures. But it also damaged a sizeable number of metopes, carved marble plaques in high relief which were integral to the architecture of the Parthenon.

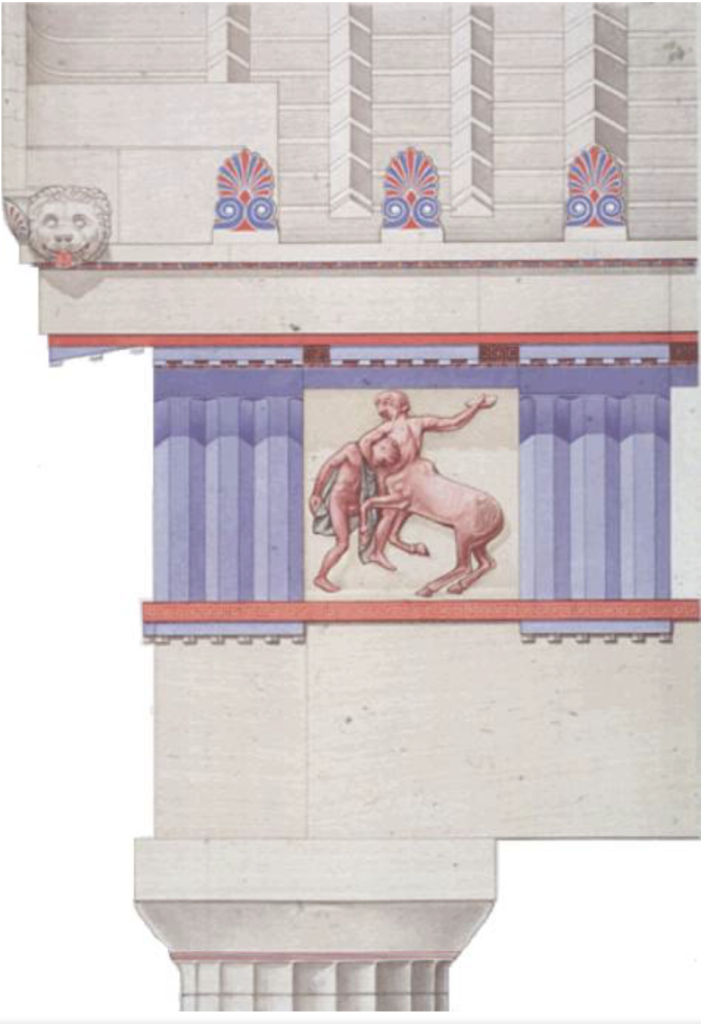

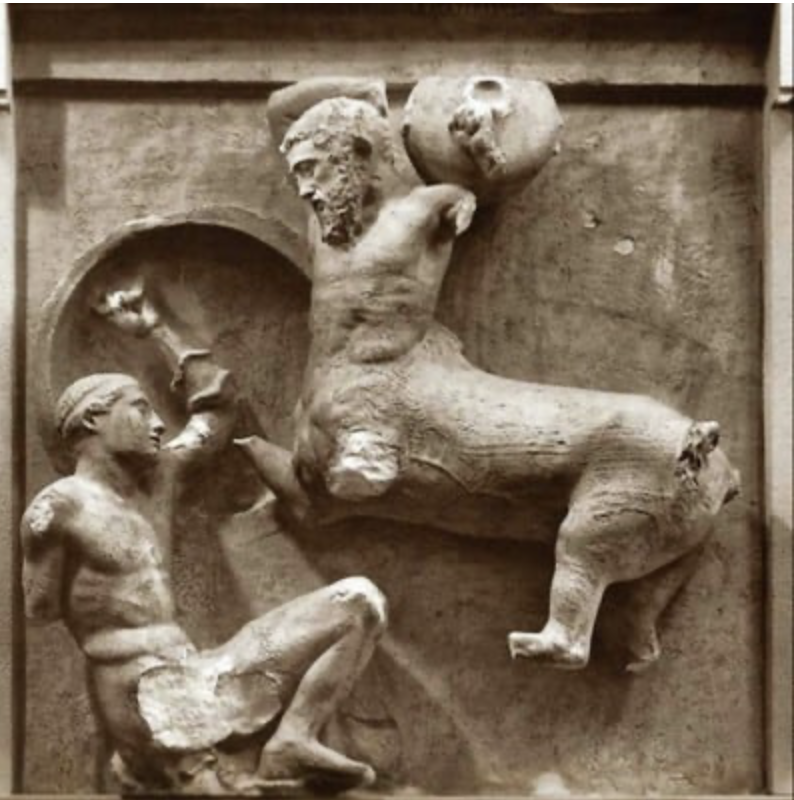

The main theme of the thirty-two metopes on the south side of the Parthenon was the Centauromachy, a mythical battle between Lapiths and the half-human Centaurs with each metope depicting either a fight between a Centaur and a Lapith or the seizing of a Lapith woman by a drunken Centaur during the mythical wedding feast of Peirithoos, king of the Lapiths.

A battle between civilisation and chaos, order and barbarism.

In 1688, barely a year after the bombardment, a Danish naval officer, Moritz Hartmann who served in the Venetian army under Morosini, is thought to have purchased two of the recovered Centaur heads from a pedlar on the streets of Athens and took them back to Copenhagen as the spoils of war.

In 1674, the French artist drew the Parthenon frieze and other sculptural decoration so that we know what the metopes looked like before the Venetian bombardment. The South Metopes III & IV are shown below.

Both heads are from South Metope IV which was forcibly detached (sans the heads) by Lord Elgin’s men in the early part of the 19th century and eventually made its way into the British Museum as part of the Elgin collection of Parthenon Marbles. This particular metope depicts a Centaur that is about to hurl a hydria (vase) from the wedding feast at a Lapith who is kneeling on the ground with his shield raised to protect himself from the imminent and potentially mortal blow.

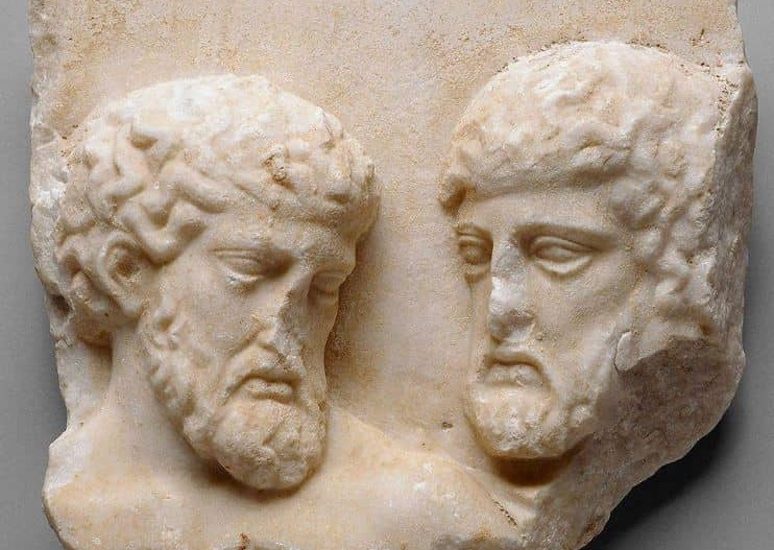

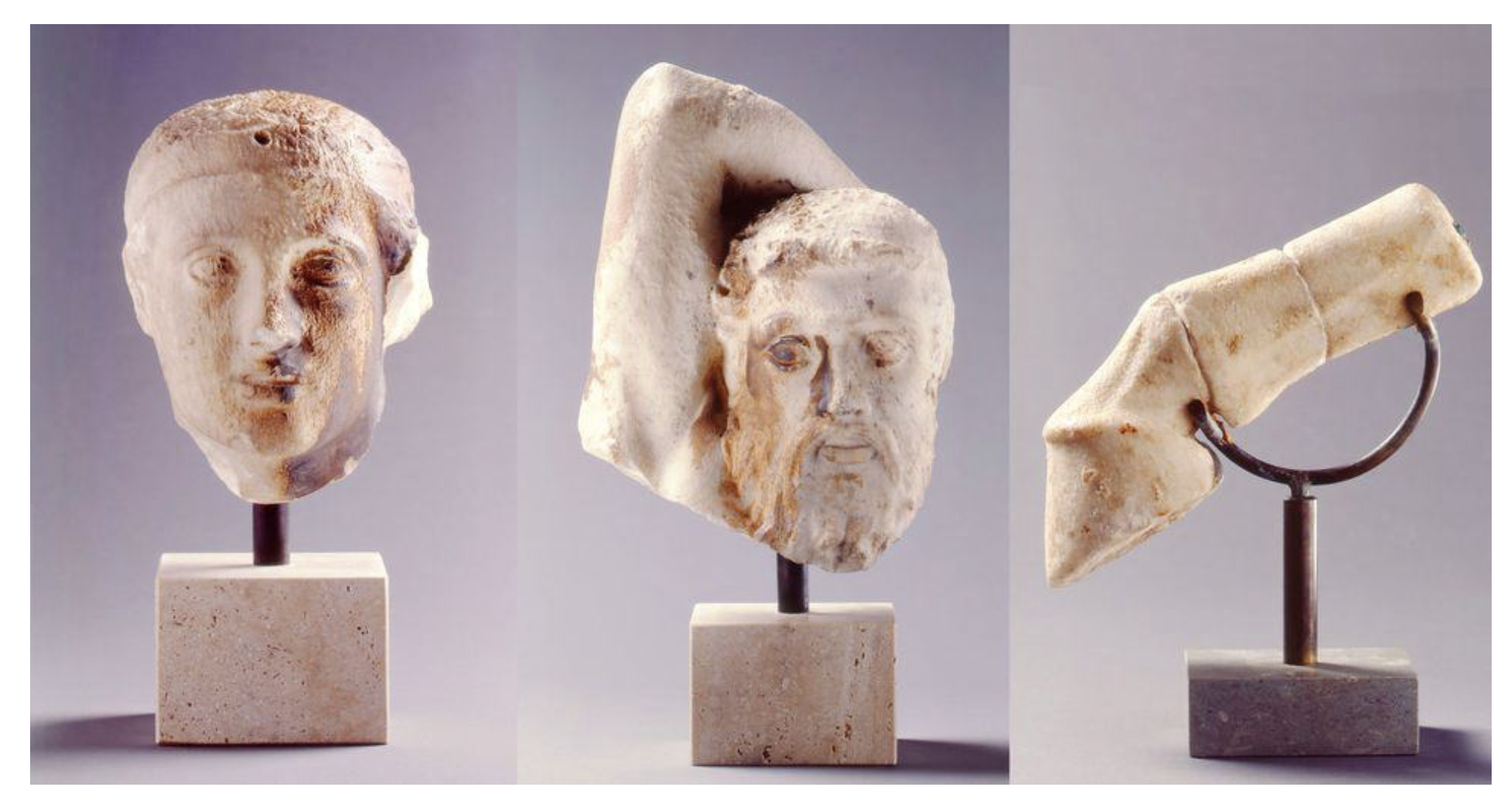

The first head in Copenhagen portrays a bearded Centaur with part of his right arm.

The other head is that of a youthful Lapith whose lively gaze and half-open mouth betray the strain of the combat.

The two severed heads are currently displayed in two solitary cabinets in the Copenhagen museum, totally decontextualized and detached from both the remainder of the metope in London and the monumental Parthenon in Athens.

Interestingly, the heads of the Centaur and the Lapith have been digitally re-imagined and re-attached to the metope through a collaboration between the British Museum and the National Museum of Denmark to show how they were created and how they should properly be viewed.

The third fragment is a portion of the leg of the Centaur in South Metope IV. It was brought to Denmark on 11 March 1835 by Christian Tuxen Falbe who had been appointed as the Danish Consul General in Greece for the purpose of collecting antiquities on behalf of Prince Christian VIII.

The exquisitely rendered Centaur’s leg actually comprises three fragments that were apparently bonded by Falbe himself. According to Dr Elena Korka in her survey of Fragments of the Parthenon Sculptures Displayed In Museums Across Europe (2017) traces of the bronze hooves of the horse and also marks of the joint between the leg and the Centaur’s body are still preserved.

Another fragment from the left hind leg of the Centaur is in the Acropolis Museum and has been adjusted to the plaster cast of the original metope which is in the British Museum.

The result is that South Metope IV, a sublime sculptural relief that once adorned the Parthenon, is today literally and metaphorically torn between London, Copenhagen and Athens.

But according to Christian Sune Pedersen, the Head of the Research Department at the National Museum of Denmark, the three fragments are of greater importance for Danish cultural history because it is important for Danes to know Denmark’s place in European history. It’s almost as though the Danes are taking a leaf out of the British Museum playbook which has consistently argued that the sculptures in the British Museum tell a different story in London because they have been in the British capital for over 200 years.

It is also claimed that the Danish National Museum evaluates inquiries on objects based on various criteria, including the object’s origin, history, manner of acquisition and its significance for the country of origin.

The museum’s purported justification for retaining the Parthenon fragments cannot withstand proper scrutiny, certainly not in the case of the two heads which are displaced cultural heritage items recovered as spoils of war.

As the late and revered Greek archaeologist, Alexandros Mantis, wrote in his book Disjecta membra: The looting and dispersal of the ancient artworks of the Acropolis:

“The sculptural decoration of the Parthenon survived until the time of the explosion almost intact except for some damage caused by the Christians when the temple was converted into a Christian church. The destruction (in 1687) and abandonment of the monument was also the starting point for the looting and pillaging of its sculptural decoration … transforming the long majestic colonnades of the monument into voluminous ruins, consigning some its most prominent architectural sculptures to oblivion.”

It is not the first time that Greece has made a request for their return. In 2003, even before the completion of the construction of the new Acropolis Museum, the then cultural attache at the Greek Embassy in Copenhagen, Georgios Fotopoulos declared:

“The two Copenhagen heads are of great symbolic significance for the Greek people, they are part of an entity, they belong with the rest of the Parthenon sculptures. It would be a splendid gesture on the part of Denmark to offer to return them .. Regardless of when or how Denmark got them, the two heads belong in Greece.”

At the time, it was reported that the Danish National Museum’s reaction was non-committal, with the then curator Peter Pentz stating that in principle the museum decides on returning artefacts on a case by case basis after receiving a formal request.

Significantly, the National Museum of Denmark has participated in the return of some very notable cultural artefacts, including the 1971 return of rare Islandic manuscripts to Iceland, the Utimut repatriation in 1984 of approximately 35,000 archaeological and ethnographic artefacts to the Greenland National Museum and Archives, as well as the repatriation of Maori human remains to New Zealand.

More recently, in 2014, the Danish newspaper Kristeligt Dagblad published an extensive article calling for the return to Greece of the Parthenon Sculptures exhibited in the British Museum.

The catalyst for this article was the exhibition ‘Transformations: Classical Sculpture in Colour’ on view at the Glyptotek in Copenhagen, in the context of the video recreation (referred to earlier) of the reunification of the south metope in the British Museum with the missing heads displayed in the National Museum of Denmark.

Its author called on Denmark to set a “good example” by returning the two heads so that they can be restored to their original position, adding that the copies will have the same value for us, but not the same for the Greek state, and their return would send an additional message to the British Museum.

The National Museum of Denmark is also today confronting challenges over its collection of Benin Bronzes acquired in the late 19th century after the pillaged bronze and ivory treasures were dispersed throughout Europe following a punitive British military expedition.

According to Christian Pedersen, the Benin Bronzes can be used to tell the story of how powerful empires existed in West Africa and how brutal European colonialism could be in justifying their retention. But he also tellingly added:

“Of course, the fact that the bronzes are of great value to the National Museum does not mean that they will be with us forever.”

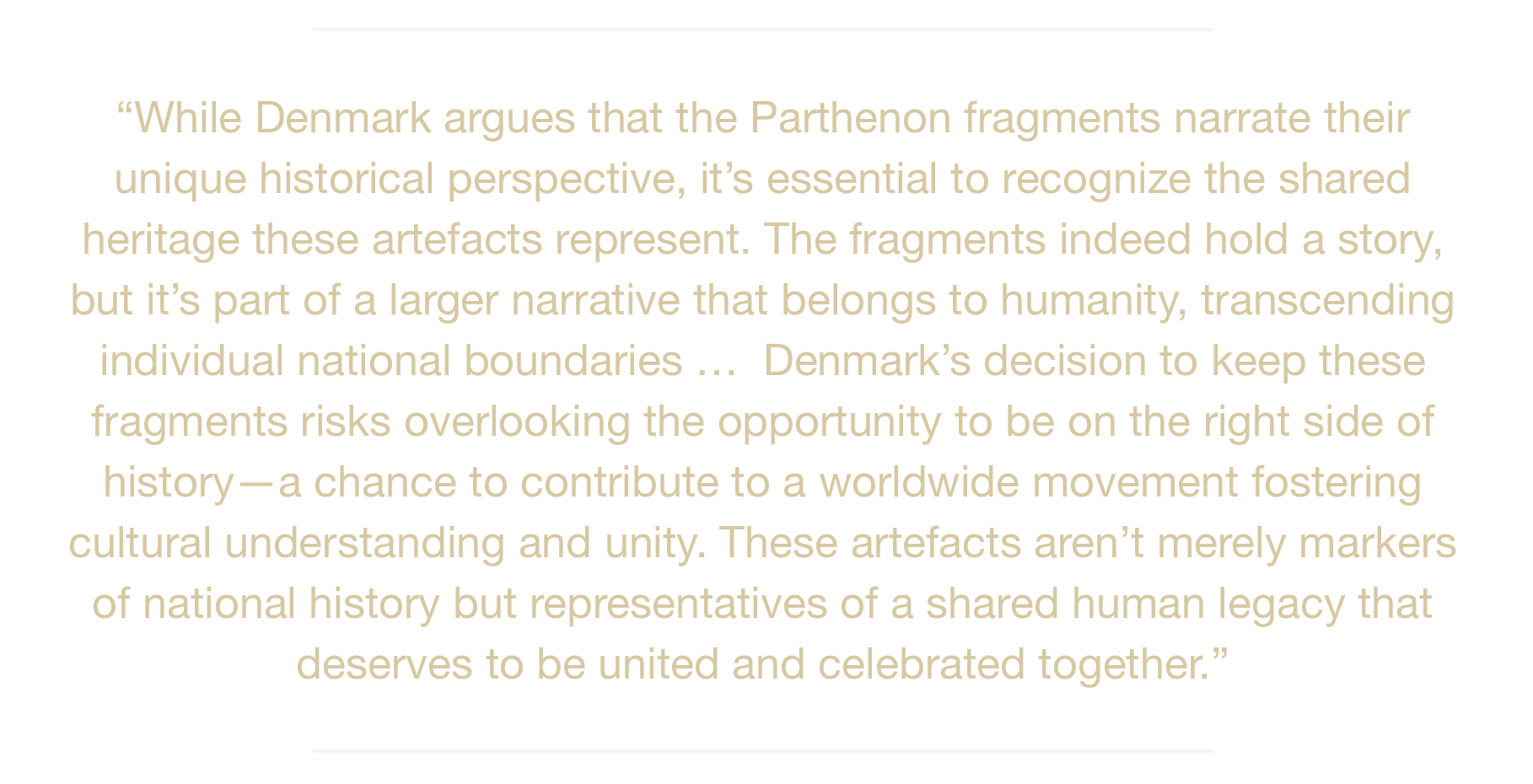

The last word goes to Alex Pistofidou, the Chair of the Austrian Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, as well as a member of the Acropolis Research Group, who is disappointed by the Danish national museum’s stance in bucking the global trend of repatriation of significant cultural treasures to their rightful place, especially after the recent prominent return of Parthenon fragments from Palermo and the Vatican and the reports of negotiations underway with Vienna.

According to the eloquent campaigner:

The time has surely arrived when the Danish government and the National Museum of Denmark need to take a more nuanced approach and explore the real possibility of an enlightened cultural partnership with Greece for the benefit of both countries as a prelude to the eventual reunification of all the known surviving Parthenon sculptures in Athens.

Only then can the enigmatic epithet from Hamlet be disavowed.

George Vardas is the Arts and Culture Editor and is also Co-Vice President of the Australian Parthenon Association and co-founder of the Acropolis Research Group.